Brewing Innovation Spaces

Fellows from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and their faculty sponsor share lessons they learned from hosting a regional meetup on November 3-5, 2016.

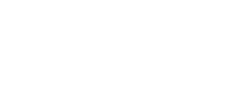

University Innovation Fellows in front of the Kulwicki Pitstop. From left: Nicole Green, Kathryn Christopher, Jim Lee, Brad Turner, David Gallegos, Elizabeth Creamer, Andrew Schilling, Magann Dykema, Eduardo De Leon, Alycia Doxon, Jonathan Cook, Alex Francis, Hannah Barton, Lydia Gregersen, Samantha Schultz, Amin Mojtahedi and Katie Dzugan (sitting)

by UWM University Innovation Fellows and Dr. Ilya Avdeev

Are you thinking about hosting a regional University Innovation Fellows meetup at your fine academic institution? Do you want to learn more about “brewing” innovation spaces? Read on…

Planning and hosting a meetup can be easily compared to reaching the top of Mount Everest for climbers or rounding Cape Horn for sailors; it’s baptism by fire that will test your team but will leave you with a feeling of joy and accomplishment. If you have any doubts, don’t hesitate. Do it.

What is a UIF regional meetup?

A regional meetup is an opportunity for Fellows to connect or reconnect with each other and with the UIF team face-to-face for several days within a driving distance (typically) of their home school. Regional meetups are much more intimate and personal than the Silicon Valley gatherings (150-300 Fellows) and they offer an opportunity to do a deep dive into a particular theme or a problem.

On September 7, 2016, nine University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Fellows (five Fellows representing three cohorts and four candidates in training) received exciting news from Katie Dzugan on being approved for hosting a regional meetup. The meeting with Katie and Laurie to brainstorm the meetup dates, timeline and agenda was scheduled for September 19, giving fellows 12 days to celebrate (11 days) and mobilize (1 day).

So what have we learned throughout the preparation cycle and the meetup itself?

Lesson 1: The University Innovation Fellows leadership team is a great asset!

With the congratulatory email from Katie, we have received detailed guidelines on how to approach the ambiguity of planning a new event for unknown number of people with no set dates or ironed out agenda.

The UIF team takes a collaborative approach to program design. The team encouraged us to seek their input early and often. They encouraged us to tap their expertise (if you have ever been to a Silicon Valley meetup, you know what I am talking about) while also experimenting with program design to create a unique and compelling offering. They offered at least one team member to be at the meetup to provide assistance; we ended up having two team members, Katie and Humera.

The BlueJeans meeting on September 19 addressed the following topics and questions:

- Meeting focus (bridges with community, learning by doing, theme)

- Dates (align with university or community schedule to maximize exposure)

- Who should we invite (Fellows, candidates, student organizations, local universities)

- How to deal with housing (hotel block)?

- How much should we charge participants ($20)?

- What are examples or benchmarks of meet-up programming?

- How to chunk up the time?

The team gave us three days to decide on the two most important things: the dates and the theme and tagline so they could promote the event through the UIF network. This brings us to the next lesson.

Lesson 2: Early phases of planning take 10x longer than you expect

The commonly accepted rule of thumb is that when you build or create something for the first time, it takes 3x times longer than planned. When you also have to decide what is that you are building or creating while building it, the time factor is more like 10x.

As the level of ambiguity reduces with time (entropy decreases and order sets in) the time factor goes down to 3x. It will never reach 1x due to the optimism bias of humans: we are very optimistic about the future and fuzzy about the past.

Our team at UWM spent several day aligning our dates with the Milwaukee Startup Week, November 1-6, and settled on the theme “Brewing Innovation Spaces.”

On September 29, a “save-the-date” email was blasted across the UIF network. What we thought would take a couple of days, took us exactly 20 days (10x at play).

We still had 35 days to plan our meetup.

Lesson 3: Setting agenda is an iterative process that consumes all remaining time

Cash is king. But to get cash (sponsorship or registration fees) you need to have a compelling story (a.k.a. an agenda). The meetup agenda depends on the list of sponsors, and the list of sponsors depends on the agenda. Naturally, the following 35 days turned into an iterative process of cycling between the two: (1) finding sponsors and (2) refining the agenda. After numerous iterations, we converged to the following sponsored events (not counting social events, such as dinners and hang-outs):

- gener8tor Milwaukee 2016 Premiere Night

- Finding, Funding, Remodeling Space (UWM)

- Rockwell Automation: tour of innovation spaces and resource mapping

- Red Arrow Labs: Tour & Workshop

- Visit Milwaukee Art Museum

- MKE Startup Week: MobCraft Brewery Tour

- MKE Startup Week: Business Model Canvas Workshop

- Make your own space worksop (UWM)

- EE computer lab re-design brainstorming (UWM)

Lesson 4: Home-brew your content

For your regional meetup, do research to use your unique resources (city, campus, people, etc.) to craft and try new exciting things with new home-brewed content instead of repeating the same Silicon Valley meetup and training activities.

For example, Milwaukee used to be a Silicon Valley of beer brewing (Miller Corr, Pabst, Lakefront, etc.). The city keeps creating new craft- and micro-breweries. One of the stops during the meetup was at the MobCraft Brewery, where beer recipes are crowdfunded allowing for folks to submit wackiest combinations of ingredients.

Lesson 5: Get your entire team on-board early and assign clear roles

Get the whole team on board and have set weekly meetings. It may help to create one key point person for the whole meetup and everyone owns pieces of the meetup. That way there are always one person that knows what is going on.

The process of organizing and running a UIF meetup can be broken down into dozens of micro-projects or tasks that interdependent and need constant coordination. Designate one “orchestra conductor” (could be a UIF faculty mentor or a seasoned UIF) whose job is to make sure that all task owners play along.

Finally, collectively map all team members’ diverse talents and assign responsibilities accordingly.

Lesson 6 (for faculty mentors): be open to switching leading/following roles

How much should a faculty mentor be involved in organizing the meetup? In our case, the Fellows took the lead in proposing the meetup and developing the theme. The Fellows took the lead on self-organizing and assigning tasks and responsibilities. The Fellows took the lead in outreach, design, set-up, logistics, facilitation etc. The mentor’s role was to keep the Fellows from falling off of potential cliffs: the financial cliff , the timeline cliff (missing the deadlines), the quality/standards cliff, etc. Things that could have been done better (from the mentor side) include setting the same expectations for all Fellows (from candidates to seasoned ones), allocating more time for visiting Fellows to share their stories, and coordinating lodging and transportation better to avoid overbooking or parking issues.

Lesson 7: Have fun!

Design Challenge: Re-imagining a Computer Lab

Introduction

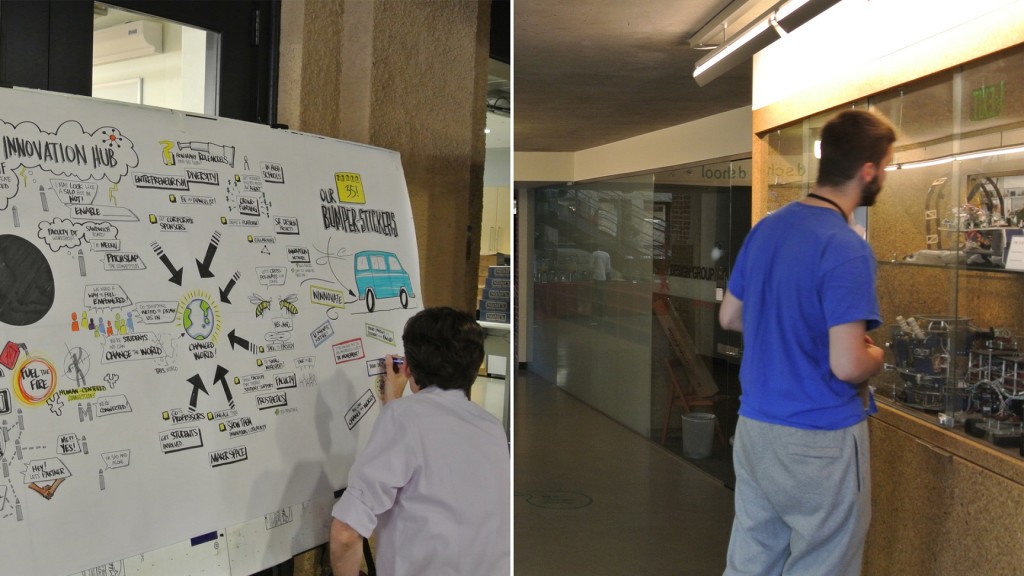

We spent two days exploring corporate innovation spaces in Milwaukee ranging from Rockwell Automation co-working space to a boutique software company in the Third Ward (Red Arrow) getting inspired from visiting Milwaukee Art Museum, and sharpening design thinking tools within architectural context at the Kulwicki Pitstop. After these space visits, seasoned Fellows as well as candidates were given a real-world challenge: re-imagining a typical UWM computer lab (EMS 270).

The problem statement was posed by Dr. Christine Cheng, Associate Professor of Computer Science: what can we do to make participants of the popular Girls Who Code weekly program learn coding in a more collaborative environment that promotes teamwork and peer-learning? Design constraints were very basic: the session has to take place in EMS 270 and participants have to have access to 30 desktop computers that are currently situated on several rows of desks.

Fellows had one hour to tackle this problem and to come up with several ideas that UWM UIF team could start building upon and eventually pitch it to the Computer Science Department for implementation.

The only instructions given to the Fellows were to use whatever design thinking tools they choose in any order they want. The Fellows could self-organize into teams (with no specific instructions) and report out in 50 minutes.

Team Ideas

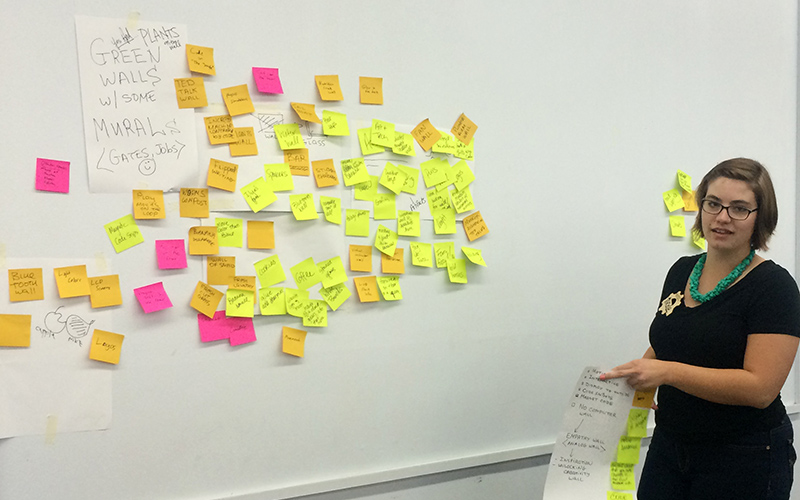

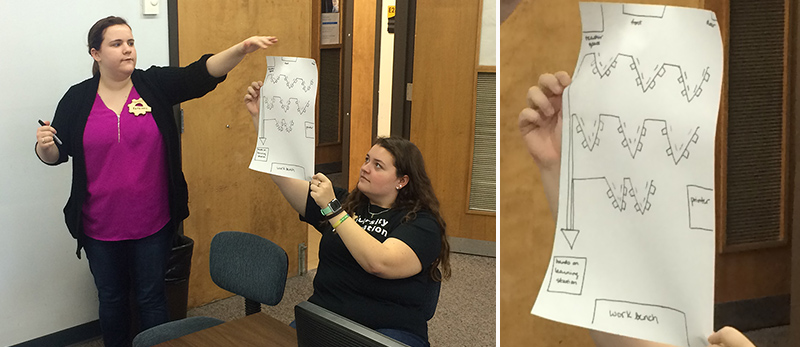

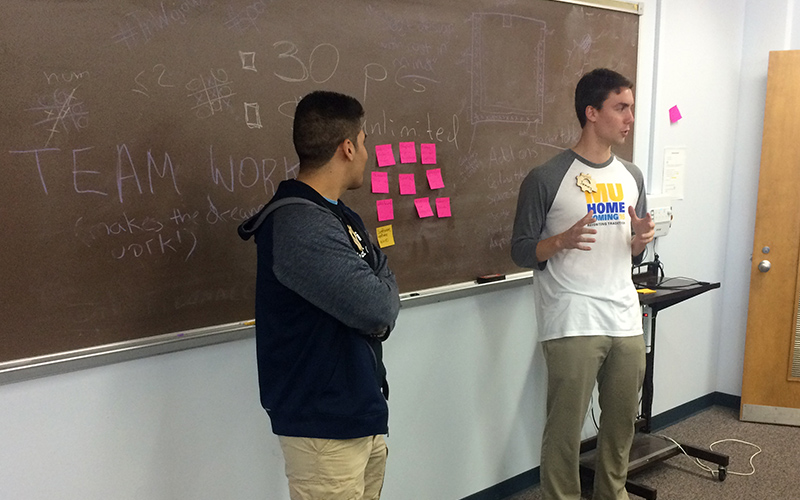

The participants organically split into five teams: two teams of two Fellows and three teams of three. Fellow Amin Mojtahedi played a role of a floating facilitator. The following pictures capture report outs and the focus of team designs.

Team “Wall”

(three members) – focused on the wall between two classroom entrances.

Key takeaways:

- First design direction: an analog wall promoting empathy and understanding of user needs, include physical objects to interact with

- Second design direction: digital wall that can display code snippets, can be controlled by code, be visible to outside hallway in order to promote interest in students outside the classrooms

- Crazy ideas: wall of smells, plant wall, fuzzy wall, an incredible machine that girls can control, magnet wall with words or coding functions to build algorithms, wall playing TED talks or movies

Team “V-pods”

(three members) – Focused on participants and on balancing peer-work with play

Key takeaways:

- Empathy: team interviewed a facilitator of Girls Who Code from Marquette (on the left)

- V-pod shaped configuration promotes peer-learning

- The classroom is separated into two areas: coding area and play area (with physical stuff)

- Striking a balance between coding and playing is one of the key design elements

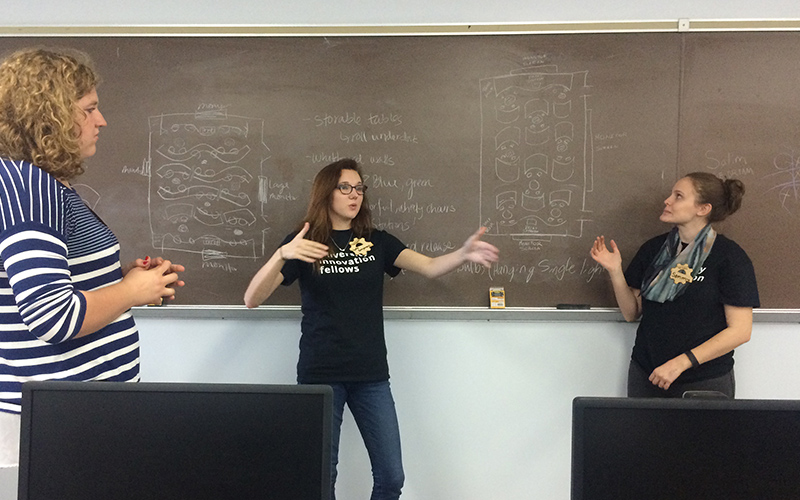

Team “Moveable pods”

(three members) – Allowed students to create their own pod

Key takeaways:

- Students can create their own pods depending on the nature of projects

- Every workstation is on wheels

- Screens to show code on all walls

- Whiteboards everywhere

Team “U-shaped Instructor Zone”

(two members) – Focused on the instructor and ability to easily move

Key Takeaways:

- Open-up room for instructors with desks around the walls

- Easy access to students

- Replace the clock on the wall

- Refresh the paint – appearance is important and it promotes certain feel

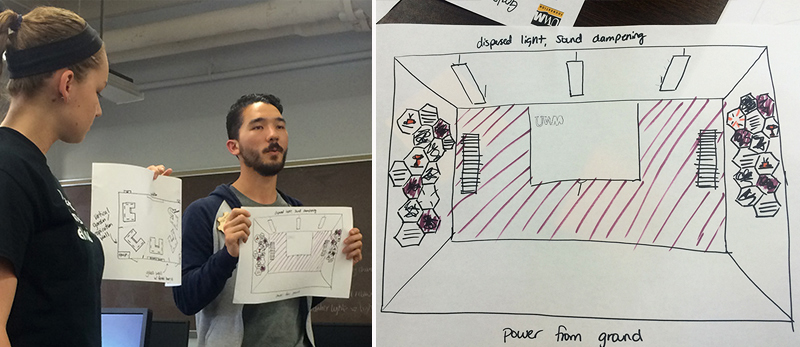

Team “Functionality”

Focused on sound, electricity and other functional aspects of the classroom

Key Takeaways:

- Soft light, damped sound

- Glass walls, vertical garden

Conclusions

Students used design thinking mindsets and tools to re-imagine an existing computer lab space. Nine Fellows at UWM now have a creative platform to build upon. This workshop introduced participants to the design challenge and helped them gain more understanding of the constraints and environment. The next step was a deeper dive into this challenge: a workshop focused on the end-users (students, girls who code and instructors) that would include all five elements of the design thinking process (from empathy to prototyping and testing).

Appendix

Here are some artifacts/tools:

UWM: www.uwm.edu

UIF@UWM: http://universityinnovation.org/wiki/University_of_Wisconsin_Milwaukee

The event was sponsored by: